A New Definition Of Movement?

Movement… we all have some affiliation with the word, whether we’re working or studying in the physical movement industry or not. I do yoga, some will say; others running, pilates, climbing etc.

Indeed it’s more than enough to have a physical practice of ANY kind (and perhaps never enough if we’re not consciously aware of what we’re choosing and/or sacrificing to do so).

The ‘Movement Culture’, started by Ido Portal, and continuing as a somewhat niche in the exercise/fitness world has its own (sort of) vague and ever-changing definitions also. It’s inclusive, yet not limited to, mindfulness, endurance, acrobatics, dance, martial arts, circus skills, floorwork, calisthenics, partner work and more.

Still, however, there is little talk of such things as communication, nutrition, digestion, blood flow, emotions, the psyche and various other ‘basic’ human processes taking place every day.

As teachers, movers, athletes, we all have our (unconscious?) biases, preferences and specialties. We can be forgiven for not addressing EVERYTHING all at once… after all, we can certainly try and do TOO much in this world, to our own detriment.

That being said, Moshe Feldenkrais, an Israeli Movement researcher and teacher, may indeed have been way ahead of his time when he broke down the term Movement as meaning, fundamentally, the processes of speaking, eating, breathing, digestion and blood flow. Take away the niche and/or specialised aims of, say, performing a 60-second handstand, running a 4-minute mile or winning an MMA fight, and our daily practice more than anything reflects these 5 key aspects of being.

It’s not a choice in fact - hence the accuracy of Feldenkrais’ definition - to eat, speak, breathe, excrete etc. We must, to survive, and therefore to thrive.

As Kilian Jornet nicely put it in a recent video blog: “performance is just the expression of health”.

Health, of course, is the primary pillar upon which all others must be built.

Feldenkrais suggests a more holistic and human appreciation of Movement as a general field of study than the IG-friendly versions otherwise available (filled with handstands, pullups, acrobatics etc… whatever easily inspires and impresses the watching audience). He was a pioneer in his day, and yet he’d have failed to become rich and famous in today’s world perhaps. Simple, natural and sustainable advice usually doesn’t sell. People typically don’t want to pay to be told to eat their vegetables, to have difficult conversations with their loved ones, to take cold showers or to meditate 60 minutes a day.

Most of this sincerely good advice is free of charge, and has been written and preached about for hundreds (even thousands) of years.

The dance, the fight, the muscle-ups, are the icing on the cake - the extra step towards being a performative, athletic and/or attractive person. We shouldn’t undermine these effects; they make life worth living after all, and provide the ‘peak’ or ladder of which all else is oriented towards. A competition can inspire conscious nutrition and a regular mindfulness practice, for example, in order to effectively tackle the task. An upcoming race inspires discipline, organisation and emotional-regulation in a way that little else can.

And yet these arenas are not the totality of life, no matter how enticing it is to live deeply inside of those worlds. The mountain top is for visiting, not for living on, as Louis CK (one of my favourite people) wisely once said.

Personally, indeed it’s hard, or even impossible, to separate the two at times. There is no real ‘point’ to dancing , running, playing, competing when it really comes down to it. And yet what is life worth without it?

And so here comes our contradiction… our (existential?) dilemma:

To what extent should / must we do the sensible thing and base ourselves in the fundamentals of good human functioning, as Feldenkrais points to? And how much should we prioritise our higher aims, first and foremost, and let the rest naturally take care of itself?

Perhaps it IS impossible to fully separate them - a fence-sitting exercise rather than any real solution. Certain classic euphemisms point toward specific other conclusions however. Lines such as:

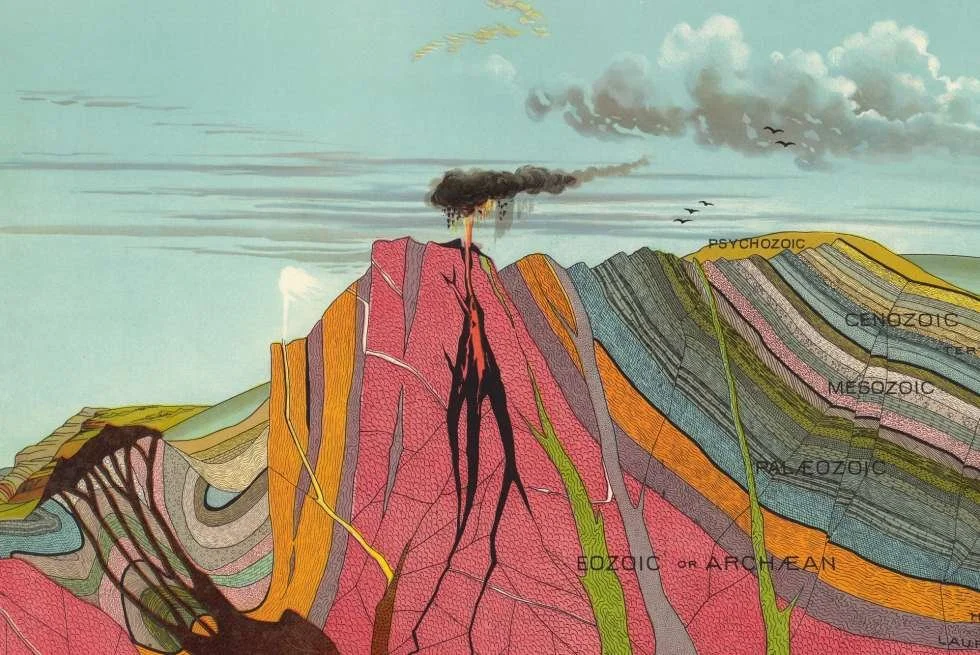

‘You can never work enough on your fundamentals’ OR ‘The wider the base, the taller the mountain’.

Feldenkrais focuses intelligently on these fundamentals of course, explaining how many ‘ordinary’ people in fact move, live, exist in better ways than the elite athletes or impressive performers we often look up to. There’s always a price we pay for specialising… in anything! A true generalist pays as little price as possible while (hopefully) still being fulfilled enough by their life’s mission and goals.

Equally, to play devil’s advocate, and perhaps contradict myself once more… Taleb’s ‘barbell strategy’ highlights the reality of any effective process of learning, change or growth. That is that one must move deliberately and intentionally out of balance in order for one’s life to find long-term homeostasis, health and longevity.

Being alive is, by it’s own nature, to decay, to use oneself up, to move towards one’s own end. How we choose to negotiate the journey is an open book, but the nature of the path is unquestionable. We must decide certain frictions, stories, angles, through which we use ourselves; for meaning, for fulfilment and even for mental and physical health. Sit still long enough, after all, and all of us will be pulled powerfully towards doing something - it’s beyond our control.

This could be binge-watching Netflix or it could be charity work; marathon running or novel writing. We don’t have a choice but to invest, perhaps even ‘exhaust’, ourselves into something. And so we are all specialists, practically speaking. By creating and deciding for this specialised ‘smaller’ life we give ourselves something to lean into and away from; allowing us to focus deeply and, equally, relax effectively also. Hence the ‘barbell’ analogy - stiff thick ends filled with a light, thinner middle.

A holistic, happy life perhaps requires something MORE than Feldenkrais lists above - it involves a deeper, braver, perhaps riskier adventure. One that disregards, to a large degree, any appreciation of breathe, communication, digestion or the body at all in fact. By detaching fully from one’s mortality (or notions of health, movement, life etc) we find a finite success or friction that constitutes our deeper destiny or fate - something that’s actually worth dying for. For some this might be writing, painting, sculpting etc; for others basketball, weightlifting, cycling.

To forget one’s ‘self’ through activity is to know oneself perhaps… and besides… people sometimes live long fulfilled lives without any conscious thought at all regarding their breathing, digestion or speaking habits whatsoever.

Still, however, the (unconscious?) paradigm of self and self-fulfilment remains our focus here, and perhaps it shouldn’t!

I, like many of you reading, have grown up with a general cultural ‘attitude’ of importance towards myself, my dreams, desires, ambitions, needs etc. It’s rare to find such an ‘ethical’ person these days, whose entire life is shaped around rules and ideals nothing to do with their own personal (selfish?) needs and wishes. The decay of modern religions and proudly-patriotic nation-states has perhaps most contributed to this.

In turn, spirituality has emerged as a necessary antidote to the emptiness and confusion that comes from too much of ‘oneself’ (think yoga and mindfulness now available in every town in England).

Does Feldenkrais’ stripped back, rather holistic definition of ‘movement’ do its ‘higher’ job of actually allowing us to get out of our own way?

Meaning that many specific ‘health’ / ‘body’ focuses might contain a certain vanity or self-interest that don’t in fact serve the world, or even ourselves, at the deepest level?

Did the drug-filled, alcoholic genius writers of our past in fact do a disservice to us and themselves? Did the aggressively-competitive, compulsive athletes we look up to and worship live fickle, empty lives? Might we all have been better off had they simply ate well, spoke honestly, meditated and took brisk country walks?

Buddhism, and such other spiritual pursuits, are fully legitimate. Personally I’ve found them incredibly helpful and enlightening on many levels. And yet there’s a reason Alan Watts reminds us constantly of the ‘pinch of salt’ needed in the soup… the little bit of crazy or madness that perhaps even ‘prevents’ such followings as Buddhism from becoming tyrannical or ‘too powerful’ in its approach.

The mud in each of us is from where the lotus flower grows. Only a highly non-spiritual person can truly feel and experience the benefits of Buddhism in the same way I might taste the subtle notes of a wine or whisky better than an alcoholic (or even wine expert) might. The separation is what, in the end, completes. Think the barbell strategy once ore - intensities or ‘dualities’ that ultimately compliment one another.

And so can one even live for others, for the world, for God or any higher truth whatsoever without equally living for oneself? Only a living, breathing, thriving Buddha can spread the word. It’s rather limited what we can do from the grave…

And so this new (actually rather ‘old’) definition of Movement is legit; even if only to powerfully foster its opposite. With ease and simplicity comes meaningful difficulty - the best possible kind.

I’m thankful to Feldenkrais and others for reminding me of that…

Did you enjoy this blog? If so, click here to support Daniel’s work…